Jon Mark Beilue: No money, no nutrition, no hope

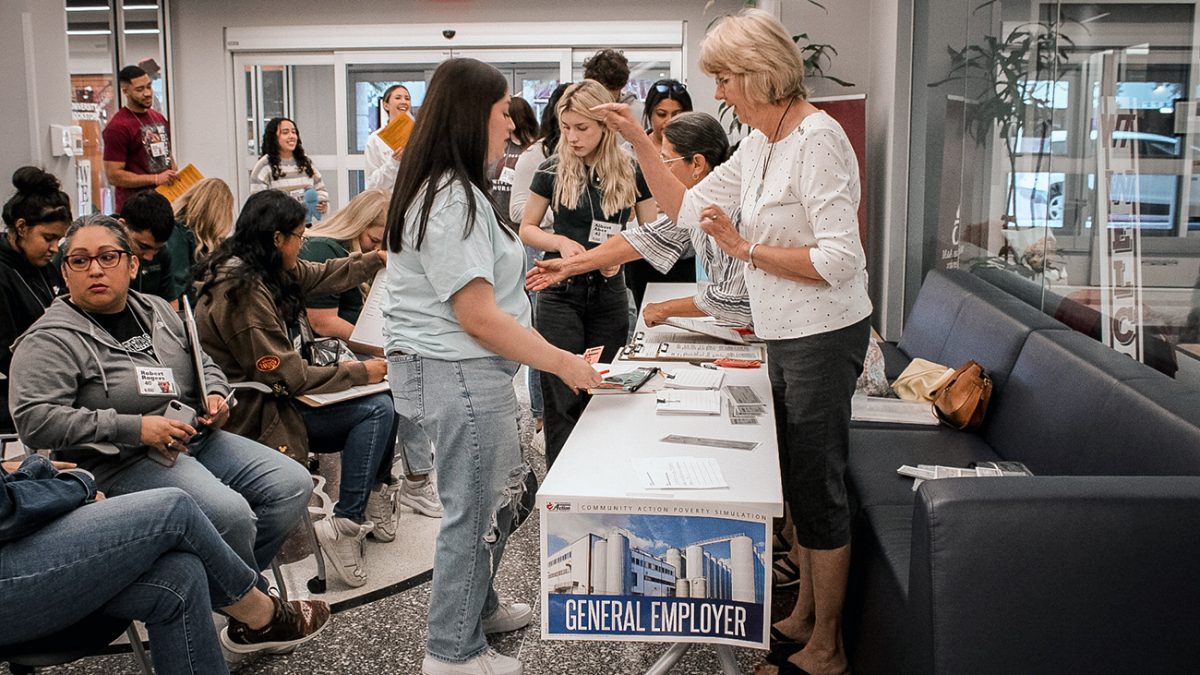

WT nursing students role play to help better manage patients

In Realityville USA, there are no two parents with double incomes over $100,000 and two healthy children. There are no serviceable two-car families, no affordable family insurance, no medical appointments to easily fit a smooth schedule.

No, in Realityville USA, as West Texas A&M University senior nursing students and students from Midland College discovered Oct. 11, it’s all about getting to the next day and somewhere, somehow fitting in medical treatment and appointments.

“Students need to be aware of the community they’re serving,” said Shawna Lopez, who has two degrees from WT and teaches anatomy and physiology at Midland College. “Having them come here and learn different scenarios and homelives their patients could possibly have is almost overwhelming.

“The simulation is so eye-opening for some of these students. Having the awareness that other people possibly face daily is something that is helpful when they serve their communities. They can treat that patient for mind, body and soul and not just the illness,” Lopez said.

Realityville USA, on this day, was in the Harrington Academic Hall WTAMU Amarillo Center, and for three hours, the fictional town’s residents—played by 60 senior WT nursing students and eight Midland College students—lived out real situations faced everywhere from small towns to large cities.

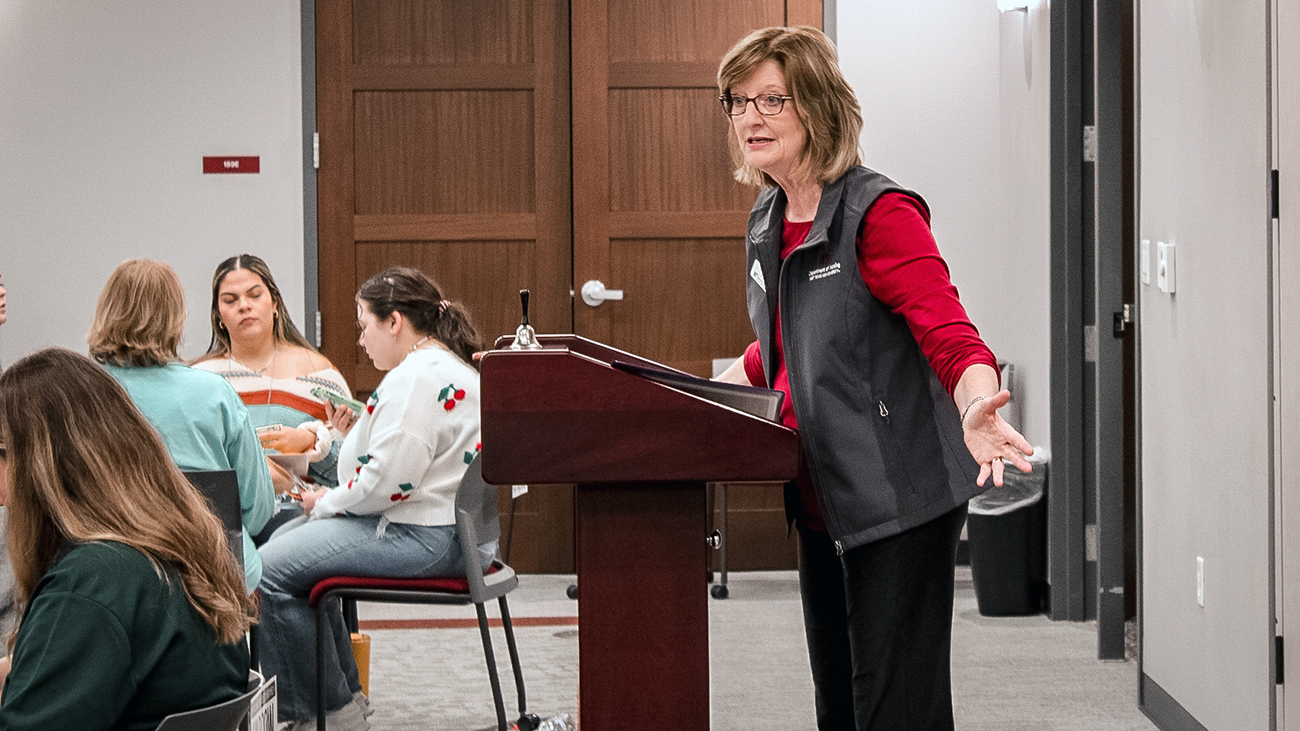

The simulation, offered every fall and spring for six years for senior-level nursing students, is under the direction of Laura Reyher, a registered nurse who serves as WT’s Baptist Community Services Professor of Rural Health.

“I spent the bulk of my career working in the community, taking care of patients in home health care and hospice care,” said Reyher, an eight-year veteran of WT. “There’s kind of a newer term we now use in my realm of nursing – ‘social determinacies of health.’ It goes by the acronym of SDOH.

“What that means is our health is a compiling of more than just skin, bone and blood. It’s directly impacted by the safety and security of the homes we live in. How adequate is our nutrition? Often good nutrition is not affordable. Those living in low income often live in toxic stress trying to take care and feed their children while getting to their jobs.”

In 2015, Reyher participated in facilitator training in the program in Springfield, Missouri. Participants in the simulation are given a profile of a low-income family member. They spend half a day navigating the obstacles that confront many in their daily lives. Her profile, randomly selected, was that of an 82-year-old Hispanic grandfather.

Reyher was impressed enough with the simulation and what it showed nursing students that the program was purchased from the social services department of the state of Missouri, which originally produced and copyrighted the simulation.

“I want to impact the viewpoint of our nursing students to understand when a patient can’t buy their medicine, or their nutrition is not good, or they didn’t get to their doctor’s appointment or therapy session because if they miss one more day of work, they’ll get fired,” Reyher said. “These are real-life issues. So, we need to be a lot more empathetic and use the full scale of health care (including) social workers and case managers to help.”

Taylin Jaeger, a senior nursing student from Pampa, was not Taylin Jaeger, at least not on this Wednesday morning. She was Al Aber Jr., age 10. Al’s dad was laid off from work four months ago and cannot find a job. His unemployment benefits ran out.

His mother is a full-time receptionist. His sister, Alice, 16, is pregnant. Al watches his younger brother, Andy, 8, because his sister spends all her time with her boyfriend.

His family has a home mortgage. There are two cars, one unreliable. Mom has health insurance, but it’s too expensive to cover anyone else. Bills for the month are going to total $1,500.

“Some of it is really helpful to see different family dynamics,” Jaeger said. “Every family is different. Honestly, we all struggle. My semester has focused on what resources the community has to offer.”

Jaeger doesn’t have to role play to understand financial challenges. She has not seen Charlie, her husband of nearly two years, in six months. He is a welder on a project in Wyoming. Their mortgage is $1,200 monthly. She spends $120 a week on gas commuting from Pampa four days a week.

Students drew from 26 different family profiles, running the gamut from grandparents raising grandkids, to unemployed father, to single parents, to a teen mom and young baby. The morning was spent learning how to live and manage health issues on a fixed income.

All around the first floor of the Amarillo Center, students visited a mortgage and realty business, a communication action agency, a general employer, the police department, Food-A-Rama Super Center, Trust National Bank, the public school, social services, Big Dave’s Pawn Shop and a place for a payday advance.

Stephanie Unger from Clarksville, Tennessee, was given the role of Winona Scott, a 52-year-old grandmother who works as a cashier. Her husband is diabetic and not working. They raise their two grandkids, ages 9 and 7, because their mother—Winona’s daughter—is in prison.

“It’s eye-opening,” Unger said. “Everything costs money, and they don’t have a lot. I couldn’t buy groceries for two weeks.”

The objective is to have future nurses understand that patients often have considerable baggage, more than could ever be seen in an appointment, and to be mindful of that background.

“I will ask more questions because a lot won’t tell you right away,” Unger said. “Be more compassionate and understanding and try to find resources to help.”

And it is about asking questions, often more than the surface ones that go to just physical health, but ones that connect to physical health.

“I don’t want us to be rolling our eyes at patients and say, ‘Why didn’t you that or why didn’t you do this?’’ Reyher said. “A patient may have diabetes so what do we need to do to help you be more successful in managing that.

“So rather that us dinging them over the head because they didn’t do that right kind of thing, we need to ask the right questions. Often, we aren’t asking the right questions: Do you have a safe place for your family to sleep at night, what does your family typically eat, can you afford your utilities? There are a lot of things we need to ask more questions about within our role as nurses.”