CANYON, Texas — A new book cowritten by a West Texas A&M University professor examines the national impact of college athletes cashing in on their profile.

In “Name, Image, and Likeness Policies: Institutional Impact and States Responses,” published by Routledge, WT’s Dr. Darrell Lovell and Dr. Daniel J. Mallinson examine new practices that allow student athletes to get paid for their likeness—and how those policies are already being stretched.

“We’re looking into what happened with the policy itself, what this means for state governments and institutions,” Lovell said. “We’re not arguing the policy, we’re looking into the impact of it.”

Name, Image and Likeness policies allow college athletes to control and profit from their personal brand thanks to state legislatures passing new policies beginning in 2019, which were upheld by the Supreme Court in 2021, then folded into new regulations from the NCAA.

While the rules technically don’t allow student athletes to be paid to play, NIL rights give the students the right to be compensated via endorsement agreements and, in some states, to hire agents. The funds often are funneled from private donors to university athletes through collectives.

“What we found was that the ethics are fluid and driven by factors within the organizations,” said Lovell, assistant professor of political science in WT’s Terry B. Rogers College of Education and Social Sciences. “Early on, our interviews painted a picture of chaos because schools were getting no guidance. From a compliance and ethics standpoint, there were a lot of schools who would rather be safe than sorry.

“But as we did more interviews and as the schools became more comfortable with these policies, the schools didn’t want to be the reason that their teams didn’t keep up,” Lovell said. “Once you open the door to offering players the chance to be paid for their likeness, immediately people started looking for ways to work around it. They’re looking to see how far they can go before they get struck down, and the answer is, pretty far.”

That’s especially true in the always lucrative area of college football, Lovell said.

“Football is always a significant factor in state policies when it comes to higher education, partly because of the money it brings in, but mostly because it’s a matter of civic pride,” Lovell said.

Lovell and Mallinson, an assistant professor of public policy and administration at Penn State–Harrisburg, also examine whether NIL collectives will negatively impact universities. Because football, in particular, is such a high-profile sport—and, therefore, more potentially profitable—collectives are most active in creating opportunities for football players, Lovell said. That could run afoul of Title IX regulations, which require schools to provide equal opportunity for all athletes, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Lovell’s research into the area will continue.

“This book lets us frame some of these conversations, figure out where we are, then figure out where we need to go,” he said. “That will be a big part of what I’m doing for the next two or three years.”

Only a handful of WT student-athletes currently have NIL contracts in place, said Paul Sweetgall, senior associate athletics director for compliance.

“Virtually all of those 15 are receiving small products or product discounts in exchange for doing social media posts,” Sweetgall said. “Student-athletes at the larger Division I schools have the opportunity to receive significant sums of money for doing exactly the same thing, but the financial opportunities haven’t filtered down to our level just yet unless the student-athlete has a contact with a business owner who is willing to help them.”

The Texas Legislature’s regulations include a requirement for five hours of financial literacy courses for all first-year student-athletes, Sweetgall said.

“This can be very helpful to them whether or not they are seeking an NIL agreement,” he said.

Lovell’s book is an example of the impactful work done by WT as a Regional Research University, as laid out in the University’s long-range plan, WT 125: From the Panhandle to the World.

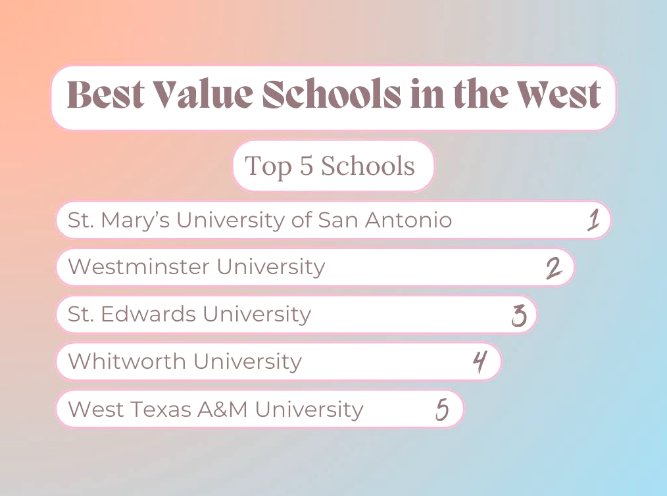

That plan is fueled by the historic One West comprehensive fundraising campaign, which reached its initial $125 million goal 18 months after publicly launching in September 2021. The campaign’s new goal is to reach $175 million by 2025; currently, it has raised more than $150 million.