COVID-19 aged the brains of adolescents

“Average brain development over three years.”

A recently published article by Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science discovered that teenagers’ premature brains have aged by at least three years throughout the Coronavirus lockdown. Similarly, children who have experienced chronic stress tend to have their brains develop at a quicker rate. This disruption in teenagers may alter their mental health and neurodevelopment.

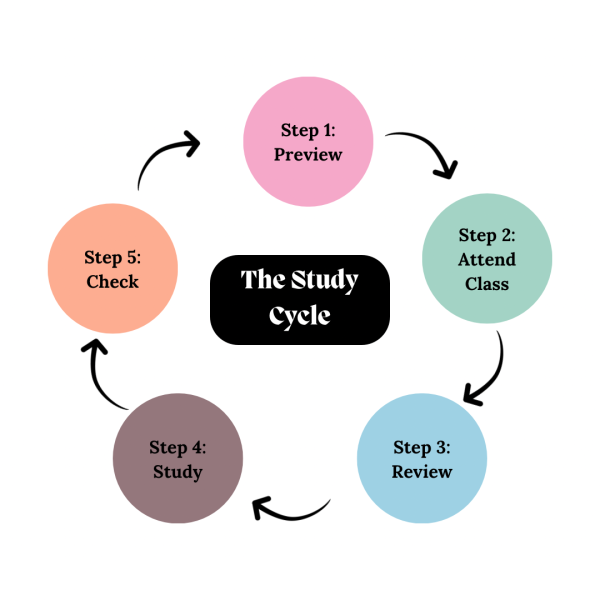

Published on Dec. 1, 2022, experts initially compared scans of the physical structures of the teenagers’ brains from before and after the pandemic began to determine significant differences. While researchers were already aware of teenagers having higher levels of depression, anxiety and fearfulness before the pandemic, the immense effects on their brains were unknown.

The pandemic has been a defining event for our generation and has become a source of adversity. Due to school closures, academic disruption and social restrictions, this analysis has discovered that the prevalence of internalizing symptoms in youth has doubled since the pandemic. Although the statistics are concerning, the implication of a child’s neurodevelopment has not been identified.

“We thought there might be effects similar to what you would find with early adversity; we just didn’t realize how strong they’d be,” said Ian Gotlib, the director of the Standard Neurodevelopment, Affect and Psychopathology Laboratory.

The study comprised 163 adolescent participants, including 103 females and 60 males from the San Francisco Bay Area. By comparing Magnetic Resonance Imaging, (MRI) scans of the group at the beginning of the pandemic and the end of 2020, the researchers found growth in the hippocampus and amygdala, areas in the brain that control access to memories, learning abilities and regulate emotions.

Researchers also noticed thinning of the tissues in the cerebal cortex, which is responsible for transporting and storing nutrients and providing support. While these changes occur during normal adolescent development, the pandemic seemingly accelerated the process.

Although a quicker-aged brain in children seems like a beneficial outcome, it, unfortunately, is more detrimental. Before the pandemic, the fast aging of premature brains was primarily observed in cases of severe childhood stress, trauma, abuse and neglect. The significant growth in teenagers’ brains since the pandemic can make them more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, addiction and other mental health illnesses while raising the risk of cancer, diabetes, heart disease and other long-term health complications.

Gotlib began scanning teenagers’ brains in 2014, where the participants would come in for an MRI scan every two years. Gotlib’s plan for overseeing teenagers’ brains was to understand gender differences in adolescent depression. The world shut down as the team was conducting the third round of scans. Instead of postponing the experiment or starting over, once the pandemic was better understood, Gotlib pivoted into researching the pandemic’s impact on the physical structure of children’s brains and their mental health.

After altering some aspects of the research, Gotlib decided to make pairs of children of the same age and gender, creating subgroups with similar puberty developments, exposure to stress and socioeconomic status.

For the most conclusive results, researchers fed their participants’ brain scans into a machine-learning model for predicting brain age and evaluating mental health among matched pairs. Unfortunately, there were more severe symptoms of anxiety and depression in the group of adolescents who had scans throughout the pandemic.

“The takeaway for me is that there are serious issues with mental health and kids around the pandemic,” said Gotlib. “Just because the shutdown ended doesn’t mean we’re fine.”

Gotlib’s study provides essential information for other longitudinal imaging studies of adolescent brains. Longitudinal development studies throughout the pandemic could discover other psychosocial impacts and create more resources for long-term mental health.

Gotlib is unsure if the physical changes in adolescents’ brains will proceed, so they plan to continue taking MRI scans every two years to gather more data.