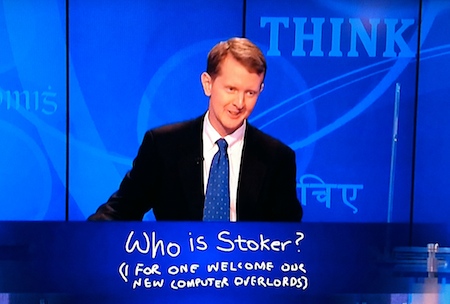

“I for one, welcome our new computer overlords,” Ken Jennings wrote in the parenthesis as he submitted in his last answer for the first man vs. machine game of Jeopardy!.

He and fellow former champion, Brad Rutter, were outmatched by the five year old who had the fastest buzzer hand in the world (despite not actually having hands), and a vast amount of answers wired into his brain.His “parents”, IBM, named him Watson after the company’s first president and began testing in 2006. He follows in the footsteps of previous IBM projects, such as Deep Blue, a chess playing computer developed in 1997.

Dr. Chris Furner, assistant professor of computer information systems at WTAMU, points out that Watson is part of a long computing legacy. Neural networks like Watson’s have been in use for 25 years.

But Watson can do much more than win game shows.

“It has leaning algorhytms that are able to make inferences,” Dr. Jeffry Babb, assistant professor of computer information systems at WTAMU, said. “If we can express it algorhymically, it [Watson] will do it [compute] faster and more error-free.”

As reported by Ian Paul in PC World on Feb. 17, Watson represents “[a] significant leap [in] a machine’s ability to understand context in human language”.

Yet that understanding had to be built on a gigantic base. Watson has around 16 terabytes of memory (4 terabytes of it being used to store content), 2,800 processor cores and 6 million logic rules for determining answers. He’s physically big, too, taking up 10 server racks, 10 IBM Power 750 servers and two large refrigeration units.

All of this was housed in its own room on IBM’s Yorktown Heights. Yes, like many college students, Watson lives on campus.

And like many college students, Watson has a long way to go.

There are still a lot of bugs to work out.

“When it got it wrong, it got it wrong pretty substantially,” Furner said.

For example, Watson was convinced Toronto was a city — in the United States. In other words, he still lacks the ability to inference all of the information crammed into his game show contestant crushing brain.

“They don’t do abstract thinking like we do,” Babb said. “It [ the human brain ] is able to adapt.”

Watson cannot adapt.

While he has proved better than his predecessors and defeated his human opponents, the Jeopardy! win does not signal the start of Terminator’s Skynet and the rise of the machines. (Despite Wired Magazine jokingly tweeting that we were on our way.)

Nor is he about to turn on us like 2001: A Space Oddesy’s HAL or Portal’s GLaDOS. In fact, Watson may be used to help man, rather than defeat us on national television.

Babb, for example, discussed Watson’s potential in medicine.

“Doctors will tell you to get a second opinion — because there’s the possibility another doctor will pick up on something they missed,” Babb said. “That’s what getting a second opinion is for.”

But if Watson could check your symptoms against his data, for example, you could cut out the middleman.

Technology Review, a blog published by MIT, speculated along similar lines. And it seems IBM is pairing up with Nuance, a leading maker of voice recognition software, to put Watson to work in health care.

The $77,147 earned on Jeopardy won by Watson earned IBM a $1 million prize that will be donated to various charities and organizations. These include $500,000 to the World Community Grid. Another $500,000 will go to a partnership between The University of Galveston Medical Branch and the University of Chicago to combat Dengue fever, Hepatitis C, West Nile virus and yellow fever. Watson will also donate some of his winnings to cancer research, HIV/AIDS treatment and clean-water systems.

In the meantime, IBM will keep working on Watson, and man can go back to playing against man.