On average, each academic year a student will spend roughly four months in the classroom, then take several weeks off for winter break before returning to their academic routine for another five months until the three months of summer break begins. So, what happens cognitively when an individual is conditioned to a routine and it becomes disrupted by a long-term break?

“So when we talk about breaks, especially summer break, the longer break, there’s a lot of research on K-12, about what is called the ‘summer learning loss,'” Dr. Ashley Pinkham, associate professor of psychology, said. “The summer learning loss is that idea that you are at one level at the end of the school year, then you spend three months not in class, so there’s a lot of backsliding.”

Since 1906, education researchers have been intrigued by the idea of summer learning loss and have devoted immense time to understanding it from the inside and out. Researchers have summarized their discoveries in three simple conclusions: the first is that the average students’ achievement scores decline over summer vacation by at least one month’s worth of learning from the previous school year. The second is that the declines are exponential for mathematics and the third is that the higher the grade you reach, the more you lose. Another intriguing factor discovered is that a student’s loss doesn’t differentiate based on gender or race.

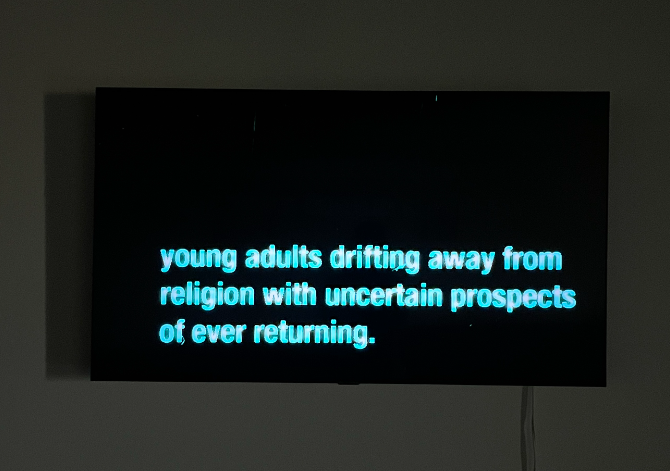

“It’s not the same across time; typically, students from high-risk backgrounds likely experience a greater loss over the summertime,” Dr. Pinkham said. “If you are from a very privileged background, you might go to summer camp, or you might go to the museum in the summertime versus kids who don’t have those opportunities, right, so they might backslide a little bit more. And there’s also a lot of research that suggests that the further along in education that kids are in and the more challenging the classes, the greater those backslides they experience. So kindergarteners aren’t going to backslide as much as a junior or senior in high school. I already knew that, but then you asked me this question in your email, and I was like, ‘Do we have research about that in college?’ and I can’t find it.”

Despite education researchers heavily focusing on the summer learning loss and backsliding in kindergarteners through high school seniors, there is yet to be anything published regarding its effects on collegiate students. Research is needed to reach a closer understanding of college students as they’re preparing for life after their academia is over, considering that most students on a college campus have their brains still developing.

“It actually got my wheels turning, like we should do this [research the effect of a long-term break on college students] and find out because I was thinking about this in terms of things like, especially, a sequence class,” Dr. Pinkham said. “One class builds on the other, so I’d suspect that you are more successful if you do it in the fall and then spring, right? But I don’t know, there’s just good reason to believe that’s right. So there is purely a loss in the summertime, especially for those sequenced major-specific courses where you have to remember the knowledge? I don’t know, but we have really good reasons to believe that.”

Although there isn’t any discoverable and published research regarding the effects on college students, based solely on how an individual’s memory operates, Dr. Pinkham thought it gives reason to believe that college students are more susceptible to backsliding.

“There’s good reason to believe based upon the analogy with K-12, but there’s also a really good reason to believe that there would be just based upon how memory works,” Dr. Pinkham said. “There’s a lot of research about the difference between massed versus distributed practice— cramming versus studying over time. Thinking about the typical student profile, a student is going to cram, get through finals week and then take a three-month break; that’s not really a recipe for remembering that material come the fall semester. However, a student who is distributing their learning in the spring semester is probably going to be better able to retain it because they were doing the optimal study strategy to begin with.”

It’s easy to believe some people don’t have to try in classes and seem to perform well. While there are outliers who have eidetic memory or auditory sensory memory, successful students are made and not inherited from genetics. To allow the brain to retain information for the future, students must review the material several times; repetition becomes their best friend to perform well. However, revisiting classes may be found in another form, as another assumption can be made that if students are actively practicing throughout the breaks, they may preserve the material.

“I would also imagine a student who is taking a course in their major where they’re using that material, even if it’s not part of the sequence, but you’re still using it,” Dr. Pinkham said. “Like students who are McNair Scholars, you know they’re doing a summer research project in their field, or students who are doing an internship in their field; if you’re using some of that material in a work or research environment, you’re practicing it and retrieving it. So, I wouldn’t expect the same amount of backsliding with them as students who crammed, got through finals, and spent three months working at Starbucks, not thinking about their major-specific content.”

For students who need to retain their academia, this can become a brutal cycle throughout their careers. The prefrontal cortex is one of the most essential functions of the central nervous system as it’s responsible for execution, functioning, planning and memory retrieval, but since the brain is fully developed in the mid-20s, college students aren’t functioning at optimal capacity. So, those who proceed and skim through the semesters may not be the most distinguished employee if they need to remember critical information about their job. One thing that can be taken into consideration to aid students’ memory is the length of a break.

“I think that certainly the length of the gap is going to matter,” Dr. Pinkham said. “We’ve got this winter break – maybe five weeks long – and then in summer, you’ve got three months off, so that may not be the best profile. There are a lot of public schools that have moved to year-round schooling, which is just three months on and one month off, or there are universities on a quarter system with 10 weeks on and one week off. You are sacrificing the long semester for a shorter quarter, but you’re also taking shorter breaks in between. It’s possible that other types of profiles are more compatible with cognition and are more compatible with memory retrieval than our traditional schooling, but at the same time, it’s really hard to transition to year-round since there are things like internship cycles and MCAT cycles that are all linked up to that nine-month calendar.”

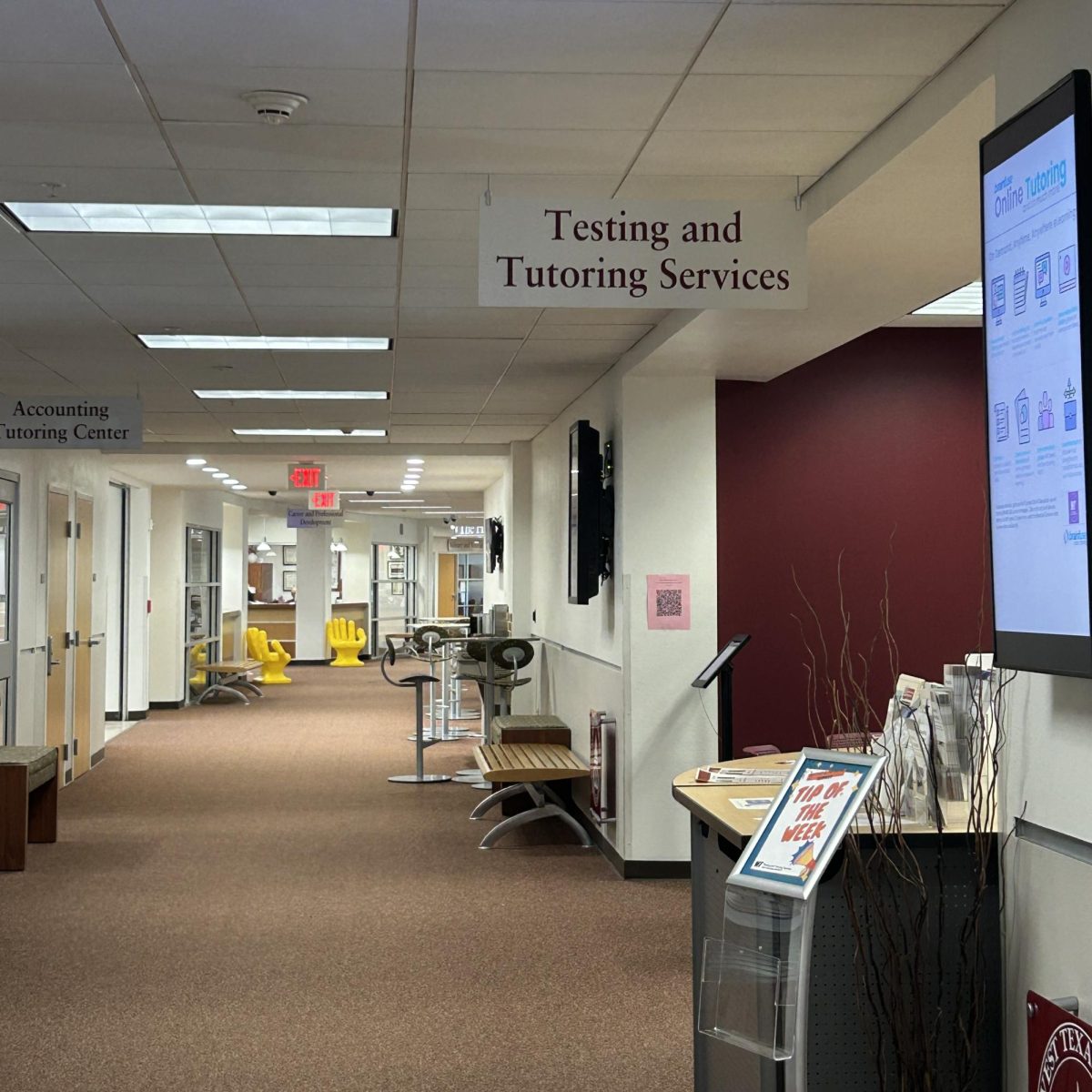

Although the effects of a break can only be presumed, it’s highly likely that if high school students are affected, then college students would be as well. Some vital resources that students can implement to aid in retaining class information during winter and summer break would be to review notes, join a research team that’s working on a project relevant to specific majors and classes, find an internship or job that pertains to their major and will utilize their knowledge or even listening to a podcast. Reviewing can be essential for when the next semester rolls around.